CHAPTER

In April the bombs started falling. Maureen's stomach started to hurt as she looked at the picture on the front page of the newspaper, black smoke pouring out of a bright orange fire, against the dusky sky. It resembled some kind of post-apocalyptic impressionist fresco, perhaps recalling some long ago battle. It was a stunning, horrible photograph that she couldn't take her eyes off.

For once, Maureen didn't know how she should feel. Politics usually seemed pretty clear cut to her. Meeting violence with violence only bred more. Everyone she had ever admired said so. Gandhi, Jesus, Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King. It was a principle worth taking even to the grave, refusing to take up arms, to take a single human life, no matter how viciously it was being lived.

She'd seen the photos of mass graves, reminiscent of those she had seen in history texts from fifty years ago. She remembered a story in Ms. Magazine, which told of an ethnic woman and her husband--Maureen couldn't remember if they were moslem or Croat--who had been captured by Serbian troops. The man had to watch as his wife's pregnant belly was cut open and their child removed and murdered, while she bled to death. Mo's stomach muscles tightened just thinking about the excruciating pain that woman must have felt. Maureen felt like vomiting. She closed her eyes, hoping to meditate on peace, believing that adding a little good energy to the world couldn't hurt, even if it wouldn't accomplish anything tangible. But all she could see was a large pregnant belly, open and bleeding like some kind of a horrible cocoon, with a woman's screams and gunfire and a weeping husband as the soundtrack. She frantically dug around in her backpack for her radio and headphones.

CHAPTER: CALLING HOME

Maureen's father talked with an accusation in his voice. Why are you doing that sounded to her seventeen year old ears like an inquisition, not a search or request for facts and it was consequently returned with what the hell business is it of yours followed by deep remorse hours and years later as she wondered how she could have been so mean to her own father who liked nothing so much as to tease or crack a joke, even if his humor found its mark on a too-fragile adolescent ego or on her mother's rage and insecurity and years later when she tried to remember when she and her father had quit talking, had learned to become strangers, she found two main culprits.

The first showed up when she was thirteen and even though she was unprecocious and didn't know about set yet, she was awkward in my awareness of herself sexually. Maureen had come across an article on incest and the first time, it occurred to her that fathers were men and could even think of their daughters in "dirty" terms and even though her father was not like that, it made her feel strange just the same and then guilty for the estrangement. But a few years later, she became privvy to information about friends whose fathers and stepfathers were "like that".

The other shrift came when she started to respond agrily to the accusations she perceived in his voice. She blamed myself for both. She had begun to try, when talking to her father, to hear the words not the tones and sometimes to repair those chasms, but they had never had the full and deep honesty it would take to rebuild those bridges slat by slat and Maureen wasn't sure if she had the courage. So phone calls were times to laugh and share news about their lives and sometimes Maureen sat in her room, on the bus, in a cafe, hundreds of miles away and tears burned in her eyes not for lost years past, but for years not yet lost, not recoverable.

The operator came back on the phone and Maureen wiped each of her cheeks with the back of her hand. "Maureen" she had after the beep. After a few moments, she heard a click like a small door opening, like a priest pulling back the screen to face a new penitent. Only this conversation would not be anonymous. Her confessors knew who she was, if not the right dispensations to offer.

"Where are you?"

"Um. I'm not sure. I'm at a pay phone somewhere."

"Well, what's the area code?"

Maureen looked around on the phone. The number above the receiver was scratched out. "Don't know."

"Why do you always call collect? Don't you have a phone card?"

"Now you won't pay for my phone calls Mom?"

"I'm just saying. I bet you call your friends with your phone card. But if we want to talk to you, we have to pay for it."

"Yeah, whatever."

Maureen heard some mumbling in the background and the click of an extra phone being picked up. Her father's voice came on. "How are you doing? Are you ok?"

"Yeah, Dad, I'm fine."

"You ok for money?"

"Well, I'm starting to run a little low . . "

"I'll put some more in your account."

"No you won't!" her mother interjected. "If she wants to run around the country like this, I'm not paying for it anymore."

"What the hell does that mean, anymore? I've been living off my savings. Remember? Job--four years of college I worked and three years after. Don't act like I haven't

been paying my own way."

"Oh, is that what you call it? Paying your own way? Finding a daddy figure to support you these last three years so you can say you're independent?"

"Fuck you."

"Don't talk to your mother like that."

"Sorry."

Her father continued. "Why are you doing this? Why do you want to run around like a bum? You should just come home and get a job."

"I just . . . this is just something I want to do, Dad."

"Why?" There was the tone. "Most young women don't do things like that."

"I'm not most people."

"That's for sure," her mother snorted. "Well, you can just pay for this little excursion on your own, young lady." Maureen heard a click on the other end.

"Why are you doing this?" her father continued.

"Are you talking to me, or Mom?"

He chuckled. "I know why she's doing this. I just don't understand you. This whole thing with your professor, and now this trip thing. What are you going to do with yourself?"

"I don't know, Dad. I don't need money. I'm going to stop somewhere pretty soon and get a job."

"What kind of job?"

"I don't know. Temping, maybe. I've got good computer skills. Maybe something in a little bookstore."

"That's what we sent you to college for? To work in a bookstore? To type in an office all day? Do you even have any work clothes with you? How are you going to go to an interview."

"Look," Maureen tried hard to keep her voice measured. Don't get annoyed. He's just asking you an innocent question. "I'll work it out, ok?"

"Did he do something to you? Did he beat you up? Did he have an affair? Did he run off with one of his new students?"

"Dad!"

"You can't go around running away from things. You can't just turn yourself off and

go disappear."

"I just needed to get away. Look, just because I'm not around everyone, being melancholy doesn't mean I'm running away. You don't know me anymore. I've been gone for seven years now."

"We miss you. How long can you do this? Eventually, you're going to have to stop somewhere and settle down. Don't you get sore from sitting on that cramped little bus all the time?"

"Well, sometimes. But then I get off for a while. I go look around, stay overnight when I can afford it sleep in the park during the day." Maureen was sorry as soon as the words left her mouth.

"You sleep in the park? That's just great. When people ask me what my daughter does, I can tell them she's indigent."

"I'm not sure I'm ready to come back. I mean, yeah I'm a little lonely. I miss Clark. But this is important."

"How? What is so important about this? I want to know how you think you're saving the world running around on a Greyhound and sleeping the park"

"By finding out about it, Dad."

"Then what?"

"I don't yet. I haven't thought that far ahead."

"See, that's what I mean. You have to start thinking about things. About things other than what you want right this minute. The world's not like that,Mo."

"Look, I gotta go. I think someone else wants to use the phone." Maureen looked across the empty parking lot.

"I'll put a little money in your account. Pay it back someday. When you get a life, ok?"

"Whatever. I don't need it Dad . . . "

"You're mother and I love you. Stay safe. I don't want to come identify your body in Nebraska or wherever you are. Ok? Just be careful."

"Bye."

Maureen hung up the phone. She noticed a large old car, some kind of old cadillac or LTD circling the parking lot. Maybe they just wanted to use the phone, she told herself. But she was too spent to take any chances. She cursed her stupidity for picking a pay phone in the middle of a big, open, empty parking lot on a Sunday morning. She stepped down the curb onto another piece of pavement, and the car sped around and entered the other lot. She clutched her backpack to her and trying not to look like she was noticing them, walked faster toward the sidewalk . If she could just get to the street, which was busy enough for people to notice her, maybe the driver(s) of the car would give up on her. She thought she had seen two people in the car, but didn't want to look too closely, for fear of encouraging their company.

Maureen walked faster, listening to the car heading towards her. Her cheeks felt hot. Stay safe. We miss you. She started to cry and broke out into a run toward the intersection. A car slammed on its brakes to her left. "Watch where the hell you're going. What are you trying to do, get killed?"

She stepped backwards onto the curb and watched her pursuer(s) drive off. Shaking, Maureen set her bag down on the grass and sat on top of it, running her hands through her scalp and crying, watching pictures of her father and her mother identifying her body.

Thinking of her mother always made Maureen think of sadness.. And then guilt.

No one over sixteen wants to be thought of as a tragic case. But in her mother, she couldn’t help but see loneliness. Despite their worry, Maureen saw her own life as happy and independent life. Suddenly, Mo’s mother had develed what seemed to her a newer dependence on her, a new need for family, as if through Mo, she could either repeat or redeem her separation from her own mother. Maureen felt her own indaequacy as a daughter, worried and guilty about leaving her completely alone to fend for herself.

When Maureen imagined her mother the young woman, she saw dreams deferred--a small, slightly older version of myself, wringing her hands and trying not to cry at airport terminals. Trying. Trying so hard.

Surrealist Doodle

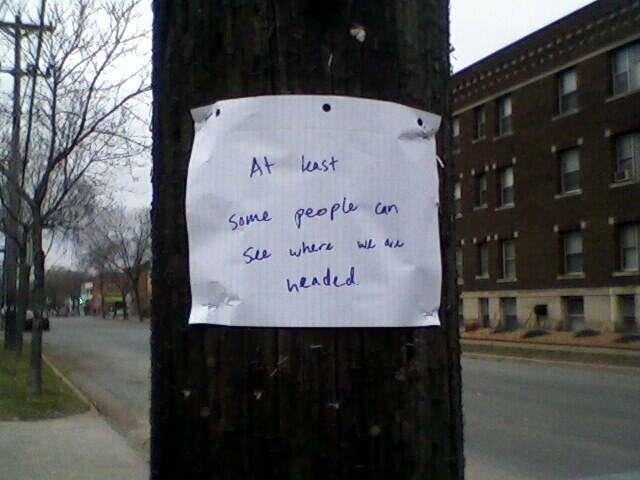

This was used as the cover of Karawane in 2006 and I have included it in on a number of bags and postcards over the years. Someone on the subway asked me if it was a Miro. I was very flattered!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment